It is the unwritten background insight underlying all international climate policy debate and negotiation that success will mean all trade is climate-smart, along with the everyday economy, everywhere.

Trade is the word we use to describe the economic, financial, and commercial relationships of exchange between nations, but we all participate in trade. Trade determines what technology we have access to, what our clothes look and feel like, and what level of food security we can enjoy—including whether we have access to health, nutritious food. And trade shapes the fiscal, economic, technological, and political lives of nations; it determines whether we have the means to avoid conflict.

Climate-smart means safe, resilient, thriving, and less likely to generate massive, sudden, unavoidable costs. Climate-smart means not only the powerful, but also the vulnerable, are less likely to be knocked out of the everyday economy. Climate-smart means informed by climate science data, capable of working intelligently in a climate-stressed world, and able to generate early warnings and organized responses sufficient to avoid catastrophic impacts and prevent destabilization of nation states.

In a climate-stressed world, finance, enterprise, and trade all need to be climate-smart.

So, what is missing from our institutions and their way of interacting that makes climate-smart trade not yet a reality but a wish for the future?

- First, the extractive model of enterprise—taking value out, without restoring or sustaining it—rewards activities that undermine climate stability, regardless of who they harm or how much cost we incur as a result.

- Second, we are not accustomed to measuring non-financial returns—the balance of secondary costs and co-benefits linked to a particular activity, or to the investment decisions that support that activity.

- Third, by focusing economic policy on the blunt instrument of unqualified GDP growth, governments have inadvertently prioritized and rewarded repeated depletion of irreplaceable resources.

So, we need:

- Non-extractive industries;

- Ways of measuring non-financial returns;

- More holistic and integrated ways of measuring economic vibrancy and success.

Such macrocritical (economy-shaping) insights, and the activities aligned with them, add up to what we call resilience intelligence. As the shift toward climate-smart industries accelerates, resilience intelligence will become a core aspect of effective decision-making at all levels.

- At the micro-scale—individuals, households, and small businesses—this might mostly mean having better choices among vendors and services, and then selecting those better options.

- At the civic or municipal level, or among medium-sized enterprises, climate-smart data systems will become critical—to establish early warning, prepare responses to climate-related shock events, and make operations agile enough to outrun major climate stresses.

- At the national and international levels, resilience intelligence will also connect to the fiscal health of nations, and to the flexibility and dynamism of traded goods and services.

Our unsustainable situation

The summer of 2023 saw climate-related shock events and extreme heat unprecedented in the history of our species. The hottest day on Earth in 125,000 years was July 3. The next day was 0.98ºC hotter—nearly 1 full degree centigrade above the all-time record, just one day after it was set. The next two days tied or broke that record again.

One major factor was another shocking anomaly in planetary science observations: For several days this summer, for the first time in recorded history, and with no evidence of such a phenomenon in the geological record, five major heat domes hovered over subtropical latitudes at the same time, forming a band of extreme heat around the planet.

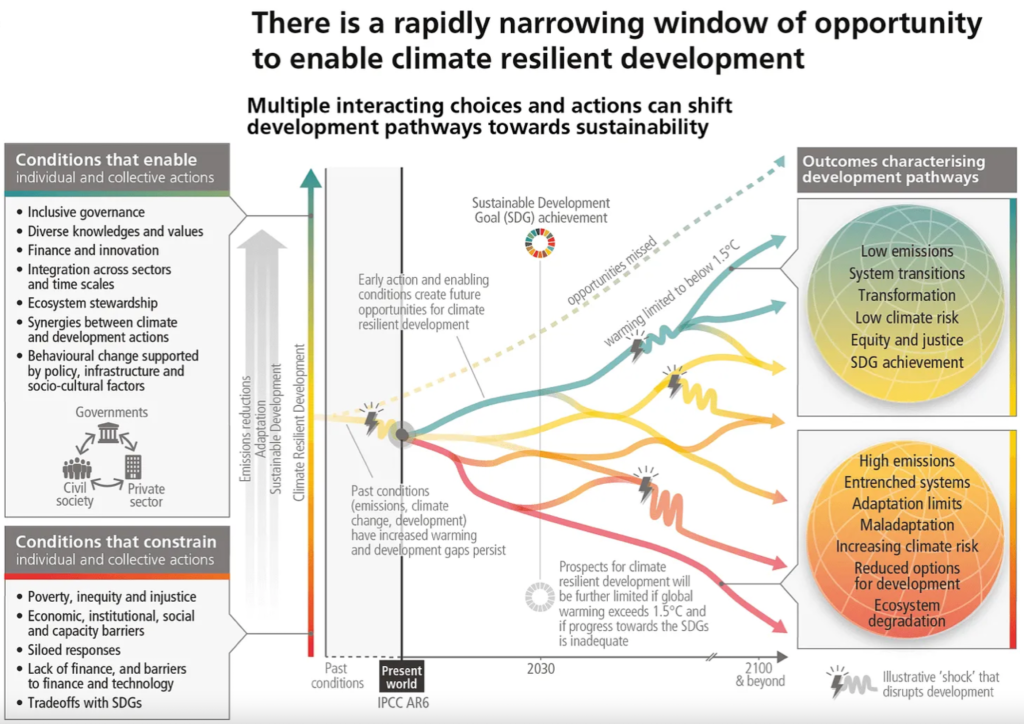

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has found in its 6th Assessment Report that the window for successful climate-resilient development is rapidly closing. Each decision that expands global heating pollution or leads to deforestation, nature loss or degraded biodiversity, makes it harder to stay on the green path toward a climate-resilient future with minimal climate shocks and related costs.

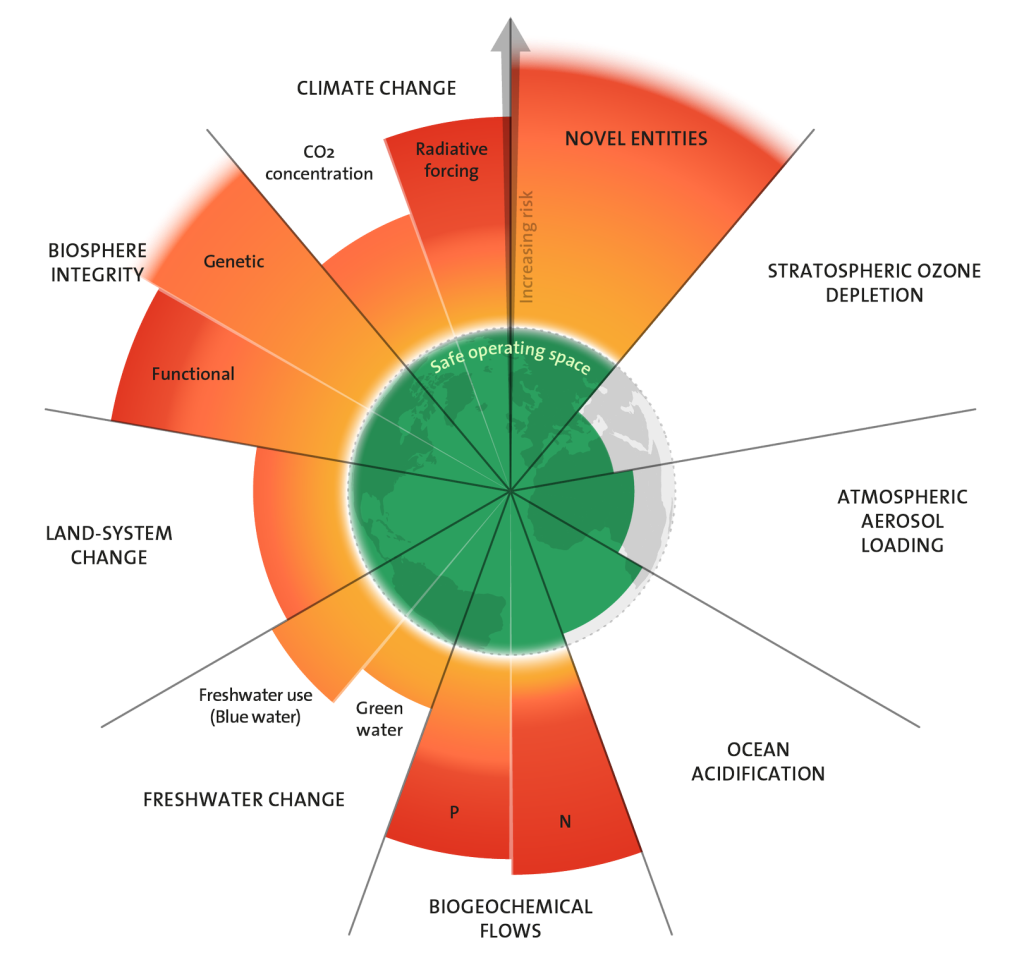

The science defining a “safe operating space for humanity” focuses on nine Planetary Boundaries. This month, as the U.N. General Assembly was opening talks, the first full scientific mapping of all nine Planetary Boundaries was published, and it found we are transgressing six of them. Breaching Planetary Boundaries means we are getting closer to losing structural elements of the Earth system on which human life depends.

Climate-related shock impacts are going to become more frequent. We know this, because the global scientific consensus is that beyond 1.5ºC of global heating, critical structural elements of our stable climate system may be lost, and because the world is still expanding overall global heating emissions.

As we have previously reported at Resilience Intel:

In 2020, the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission found that unchecked climate change would destabilize the financial system and undermine its ability to support the wider economy. In other words: climate change could cause the U.S. economy to fail in unprecedented, and possibly unrecoverable ways.

In 2021, the U.S. Financial Stability Oversight Council issued a similar finding. The report identified two broad categories of major risk to the financial system: physical risks and transition risks.

In the landmark 2022 Global Turning Point Report, Deloitte found that “unchecked climate change could cost the global economy US$178 trillion over the next 50 years”. By contrast, stopping climate disruption and achieving climate-resilient development could add $45 trillion to overall economic output. This means the shift to climate-smart trade is necessary to avoid catastrophic cost and system breakdown, and to secure future prosperity, for countries of all sizes and levels of wealth.

The future of climate-smart trade

For a long time, it has been thought that transition risks are greater if you act ahead of the curve—leaving many banks, businesses, and national governments, to let others take the early risk, so they could more comfortably enter the mainstream of climate transition. Now, however, we are seeing the costs of delay play out in real time.

Laggards may be left behind, as the brave and the lucky charge ahead. Transition risk, it turns out, is heightened by making too few preparations to be ready for the imperatives of multiple system-level transformations overtaking economies large and small.

System-level innovation is different from product-level innovation. At the level of whole industries or value chains, risk cannot be reduced by blunt instruments like waiting for the right moment or discrete case-by-case public guarantees against financial losses. Cooperative de-risking is needed, so there is reduced risk for actors across the value chain, and everyone’s investment of time, talent, and money can cost less and do more.

Climate-smart trade—trade that is successful in a climate-stressed world—will require cooperative innovation, cooperative de-risking, and cooperative financial support for innovative endeavors and for critical new services that support sustainable value chains.

It is worth noting that the International Energy Agency has found that demand for fossil fuels will peak this decade. That we have not yet reached peak demand means we should expect to build into an already overheated climate system still more dangerous future disruption, with the resulting risk, harm, and cost. The good news is that there is evidence of technological, consumer, and market trends clearly steering us away from pollution.

On the road from the Paris Summit on a New Global Financial Pact, through the U.N. General Assembly to the MDB reform discussions at the Annual Meetings of the World Bank and IMF, to the G20 Summit, and during the COP28 climate negotiations, countries should explore multilateral cooperative arrangements in line with Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement. Such “non-market approaches” to accelerated global climate transformation and resilience can provide specific, contextual, structural, and scalable strategies for climate-smart trade.

The countries and local economies that fare the best are likely to be those that start using more complex metrics to align mainstream activities with improved outcomes for people and for nature. Because unchecked climate change will impose unaffordable, possibly existential costs, the fiscal health of nations will depend on how effectively they build climate-smart priorities and practices into trade relations with other countries.

Eliminating harm and cost

Mainstreaming climate safety and opportunity means eliminating negative externalities from industrial value chains.

- Externalities are secondary costs, impacts, and benefits that are not borne by parties to an economic exchange. Negative externalities are costs that fall on third parties, or all of society, or nature, ecosystems, and the climate.

- When investments or economic activities generate profits and direct benefits but also require people, society, and nature to absorb massive unfunded costs, those negative externalities constitute a market failure—a failure of the market to price goods and services appropriately to cover all costs.

Carbon pricing measures can effectively and efficiently address the market failure related to global heating pollution. To avoid unfair competition, jurisdictions that price carbon can implement carbon-related border adjustments, to dissuade polluters from moving to pollute at no cost.

Border adjustments can be linked to emissions trading arrangements, or market mechanisms. They can also be linked to non-market pricing systems, including straight carbon emissions taxes, or fees assessed midstream (on refined carbon fuel products) or upstream (on fuel stock). When linked to revenue recycling—rebates to households and businesses or public investments or transition incentives—border adjustments can expand the reach of low-carbon goods and services, and so expand the investable opportunity linked to climate-smart trade.

Non-market international cooperative arrangements, including through multifaceted trade agreements, can support the creation of a coordinated international carbon pricing system. Such a system is sometimes described as a graduated price floor, which accounts for differentiated historic responsibilities and respective capabilities, but also helps all countries to eliminate pollution and jumpstart climate-resilient development.

Given the importance of accelerating climate cooperation, CCI released one year ago an updated outline of the PARIS Principles:

- Price pollution with a defined, steadily rising price on climate-disrupting emissions, preferably at the source.

- Add momentum. Enhance incomes; build economic value at the human scale.

- Reduce emissions effectively and accountably, by keeping the administrative structure simple and transparent.

- Internalize inefficiencies—cost and harm linked to polluting business models—incrementally, with escalating certainty and with no leakage.

- Spread by aligning price signals and supporting policies, harmonizing across borders, so pricing can be enacted country by country.

The aim is to support the optimal blending of critical ingredients of policy, incentive, innovation, and multilateral cooperation, to eliminate harm and cost and activate high-value systems transformation.

Activating high-value transformation

By supporting aligned financial regulations, integrated data systems and related information-sharing and performance metrics, as well as critical innovations in the delivery of finance to food producers that use sustainable and regenerative practices, for instance, non-market cooperative arrangements can allow groups of countries to establish climate-smart trading standards and practices.

Such breakthroughs can infuse local economies with new opportunity, while shifting production, distribution, and consumption patterns toward alignment with climate and sustainability goals. The transition to climate-smart trade will be uneven, competitive, and full of quick bursts of technological upgrading and market replacement.

As we noted in our report from New York Climate Week:

Innovation needs to be specific, contextual, and suited to improving lives and livelihoods; this also means small and medium-sized enterprises will need to provide new goods and services in context, to fill out sustainable value chains.

Transition risks are being mitigated, and opportunities expanded, through multilateral co-development and trade partnerships. Two examples of potentially game-changing partnership stand out:

- The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) aims to expand economic activity and investment return, across 54 countries, by reducing barriers to trade and harmonizing policies. While it is not a climate-focused partnership, ensuring policies align with climate-smart priorities and practices could safe African countries from massive disaster-related losses and allow for far more sustainable and resilience-building investment.

- The Africa-EU Partnership—part of a broad co-development and trade partnership between the European Union and the African Union—creates conditions for a rapid expansion of investment in climate-smart practices, and for the delivery of green goods and services to businesses, government agencies, and end users on both continents. Using non-market cooperative arrangements in line with Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement, this partnership could lead to better outcomes for people and more sustainable finances across more than 80 countries.

It is imperative that such cooperative efforts align with climate safety, shared prosperity, and macrocritical resilience. If they don’t, billions of people will suffer added risk, harm, and cost from compounding impacts of climate disruption and nature loss.

The COP28 presents an opportunity for the most open, practical, and layered discussion to date on creating incentives, strategies, and mainstream practices to support climate-smart trade as an everyday standard. A critical measure of success will be the extent to which countries emerge from COP28 with detailed plans to align domestic incentives and international trade relations with successful climate-resilient development.

Resources

Below, we share further information on specific approaches to redesigning trade relationships to secure more climate-resilient, sustainable, and inclusive outcomes for all involved.

The Principles for Reinventing Prosperity

- We are all future-builders.

- Health is a fabric of wellbeing and value.

- Resilience is a baseline imperative.

- Leave no one behind.

- Design to transcend crisis.

- Maximize integrative value creation.

More at https://reinventingprosperity.org

From ‘Capital to Communities’, the 2022 Reinventing Prosperity report

Our time of polycrisis effectively demands the most ambitious possible approach to activating available policy levers. The non-market approaches invited by paragraph 8 of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement (Article 6.8) include a vast and diverse menu of policy levers, including but not limited to:

- pollution pricing and related actions to align prices;

- recycling of revenues from pollution pricing to enhance incomes and sustain local economies;

- border adjustments and trade policy;

- central bank standards and practices;

- valuing vulnerability in financial regulations and cross-border exchanges;

- green bonds and other climate-friendly financial instruments;

- resilience measures, across sectors;

- realigned agricultural policies, to foster nature-positive and health-building food outcomes;

- coordinated transition pathways and enabling policies and investments.

Activating these cooperative engines for climate-resilient development marks a new stage in the evolving strategic seriousness of our collective response to the climate crisis. We need openness, creativity, a focus on genuine cooperation, and standards and practices that deliver high-integrity verifiable interventions that improve conditions for people and foster the health and resilience of natural systems.

More at: https://resilienceintel.org/capital

From the CCI Blue Note on Non-Market Approaches

Non-market approaches are a natural extension of relations between countries. That such arrangements are urgently needed, overtly called for in agreed international law, capable of supporting much-needed reform of international financial arrangements, and applicable to local, national, and international imperatives, means there are no excuses for not moving to create the best-case NMAs.

Those best-case NMAs should support:

- rapid and accelerating decarbonization (OMGE),

- contextual and evolving adaptation and resilience measures,

- active reduction of vulnerability, especially for the most vulnerable, and

- the steady and increasing mainstreaming of climate-related activities across the whole economy, including through improved trade relations and international finance.

More, including examples of non-market cooperative arrangements, at: https://cciblue.com/non-market

From the Good Food Finance Network report on Innovative Collaborative Funding

Reducing malnutrition and obesity provides a compelling business case for companies while generating economic growth and tax revenues for nations. A Chatham House study, ‘The business case for investment in Nutrition’, highlights that businesses in ‘low and middle-income’ countries collectively lose between $130 billion and $850 billion a year through malnutrition-related productivity reductions. That equates to 0.4% to 2.9% of their combined GDP – a massive economic burden.

These profitability losses curb companies’ abilities to invest, create quality jobs, support ancillary businesses, and contribute tax revenue. In turn, this hampers fiscal health, economic development, and political stability.

By incentivizing industry to deliver nutritious, affordable food, governments can unlock a virtuous cycle. Companies would gain financially while also tackling malnutrition, obesity, and diet-related diseases. Citizens would have better access to good food and good jobs. This is a win-win scenario for strengthening business, uplifting society’s welfare, and boosting nations’ fiscal positions.

More at: https://goodfood.finance/2023/09/20/publicfinanceicfm/

On building the Good Food Finance Facility

We don’t have time to follow the energy transition trajectory, over decades; we need to start mainstreaming good food finance now. Public, private, multilateral, and philanthropic financial actors need each other to extend catalytic investments to achieve wider transformation. The trade implications of rapid food systems transformation mean caution will rule unless there is a global support structure for innovative co-investment approaches.

The Good Food Finance Facility (the Facility) will shift and provide expanded access to finance, primarily through 1) facilitated co-investments, enabled by 2) bridging funds, 3) development of tools and policies (instrumentation), and 4) mutual accountability systems. Mutual accountability will be grounded in a Good Food Investment Framework—guidance developed jointly with the U.N. Development Program—and multidimensional data and metrics supported by the Integrated Data Systems Initiative.

The goal is to rapidly expand both catalytic and mainstream finance for healthy, sustainable food systems, supporting innovation across value chains.

More at: https://goodfood.finance/workstreams/cip/

Further Reading

- About Article 6.8 non-market approaches to international climate cooperation

- Consultation on Priorities for a Livable Future

- Distributed multi-scale resilience-building finance is urgently needed

- Earth Diplomacy Leadership Workshops — Register here

- Evolving World Bank mission and practice to support climate-safe integral human development — notes and priorities from CCI

- Food, Finance & Democracy Project

- Good Food Finance Facility — a co-investment platform for food systems transformation

- Integrated Data Systems Initiative — 5-year sprint to deliver mainstream multidimensional metrics

- NDC Collaborative — stakeholder engagement to enhance national climate action strategies

- PARIS Principles to Accelerate Cooperative Climate Resilience