Briefing note for negotiators, observers, Earth Diplomacy Leadership Initiative participants, and relevant institutional arrangements at SB58 and on the way to COP28

Key Messages

- Non-market approaches (NMAs) in line with Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement are cooperative best-future strategies.

- Complexity is opportunity – Climate policy needs roots in everyday life and should interact and compound each other’s positive effects; engage stakeholders to accelerate action.

- ‘Integrated and holistic’ means working across conventions and across the whole economy to achieve multidimensional sustainability. Act in more places to make more good happen.

- No excuses – Low ambition is irrational and unaffordable; design national and cooperative measures to be engines of ambition, mobilization, and wellbeing.

Initial Outlook

Citizens’ Climate International operates with the understanding that:

- A livable future is a human right.

- The climate crisis is complex, affecting and affected by nearly every area of human experience.

- That complexity is both a challenge and an opportunity.

- Engagement with stakeholders is necessary to raise ambition and mobilize effectively.

Climate destabilization undermines human security in all dimensions. Climate crisis response cannot be confined to one action, one issue, or one moment in time. Education, health, public safety, food systems, infrastructure, and disaster response, are all part of the climate resilience project. What is on the table in the United Nations Climate Change negotiations is the question of whether people and ecosystems will have access to health, wellbeing, and security, in the future, in every region.

This is why our finance note for the SB58 calls for transforming finance to make human experience climate-safe. It is also why we emphasized in our Capital to Communities report the role of stakeholder engagement to more quickly and precisely identify needs, risks, and capabilities, to raise overall climate action and investment ambition, and to accelerate effective mobilization of resources.

In the run-up to the SB58 round of negotiations, we co-convened a series of Earth Diplomacy Leadership Workshops with The Fletcher School at Tufts University. Emerging insights from those workshops and input from the CCI network brought the focus to key areas of interest to follow in the process:

- OMGE (overall mitigation of global emissions) – Paris Agreement standard that international climate cooperation should accelerate the pace of global decarbonization.

- NCQG (new global climate finance goal) – Aim to step up global commitment of at least $100 billion per year in climate finance (that commitment was established in 2009, was to be filled by 2020, and is only expected to be reached in late 2023).

- GGA (the Global Goal on Adaptation) – Can the community of nations reach agreement on an overarching goal for reducing climate risk and harm that is clear and universal enough to raise ambition and accelerate action in all areas?

- GST (the Global Stocktake) – How are nations, and the community of nations collectively, performing on the mandate of the Convention (to avoid dangerous climate change) as redefined in the Paris Agreement? What must happen to ratchet up ambition and accelerate mobilization to meet the need?

- Finance (mobilizing resources) – The key question is how broadly, how quickly, and how inclusively expanded finance can be mobilized to support mitigation, adaptation and resilience measures, and efforts to avert, minimize, and address loss and damage.

- Food systems (agriculture, food security, land use) – Can the wider food system, including impacts on nature, water, biodiversity, the ocean, and subsidies and trade, be transformed through climate-smart finance, policy, and innovation, for the benefit of even the most marginal front-line communities?

- Transitional Committee on the Loss and Damage Fund – Optimal outcomes would allow the new Fund to get to work quickly and inclusively, deliver aid to marginal and front-line communities, while existing funds and institutions expand their own related efforts.

- Non-market approaches (to international climate cooperation, under Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement) – Could be the engine for raising ambition, activating national plans, and mainstreaming climate-smart practices.

- ACE (Action for Climate Empowerment, grounded in Article 6 of the Convention and Article 12 of the Paris Agreement) – The degree to which Parties use ACE to deepen and strengthen climate action in all areas may determine whether they succeed as nations through the transformation.

The stakes are nearly existential in all of these areas. Best outcomes are worlds away from the risk inherent in any further slow-walking of global climate progress.

On Friday, June 9, we held an in-person check-in chaired by Carlos Alvarado, 48th President of the Republic of Costa Rica, now a professor of practice at The Fletcher School at Tufts University. That session yielded some critical insights on how the process was evolving to support shared success:

- Just transition discussions increasingly emphasize radical collaboration around concrete improvements to living conditions.

- The negotiating space is expanding, as ever larger numbers of observers seek to play a role in the mid-year technical meetings.

- A shift toward systemic conversations and planning is happening, and it should be welcomed.

- Economies need to diversify: that will mean new kinds of opportunity, for more people, and greater systemic resilience and agility.

- People, culture, land, and human impacts hold increasing importance for negotiators and decision-makers, as they move from concept to implementation.

- The breaking down of institutions: Worsening inequality and increasing geophysical insecurity are leading to disruptions that test the relevance and fitness of institutions.

- National policy, regional dynamics, and geopolitics are fluid, and have been moreso recently than usual.

- Incentives are critical—to steer through political headwinds and to ensure solutions are both practical and moral.

And the headline takeaway: inclusion drives ambition.

Below, we break down progress made and ongoing discussion emerging from the SB58, under four areas: Ambition, Mobilization, Cooperation and Engagement, and Prospects for COP28.

Ambition

Maybe the most concerning signal from the SB58 is the fact that the agenda for the meetings was only formally agreed on the next-to-last day. Some argue, however, that this wrinkle in the process actually reveals a rising awareness of and commitment to getting down to business, as the negotiations went ahead for 10 days without the formal adoption of the agendas, so needed work would not be further delayed.

Whichever side one is on in this procedural debate, the SB58 negotiations left a lot of work unfinished, while nations remain deeply divided over who needs to do what to accelerate the pace of climate-resilient development.

Mitigation (OMGE)

There was not a concrete textual agreement to accelerate overall mitigation of global emissions. While discussions in the areas of energy policy, finance, technology transfer, and national Paris commitments (NDCs) emphasized the need for accelerated low-carbon development, no formal agreement was reached on clear standards for co-decarbonization strategies that allow developing countries to advance economically while overall emissions fall. Real progress is needed on such cooperative approaches to higher ambition, to achieve transformational outcomes at COP28.

Given there are no technologies currently capable of decarbonizing the atmosphere and ocean at the scale required to reach net zero, successful mitigation in line with the mandate of the Convention (“to prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”) will require:

- the near total elimination of all sources of carbon pollution;

- widespread restoration and conservation of ecosystems.

Neither of these are happening at the pace or on the scale required, and the SB58 did not produce an agreement that the COP28 will formally recognize the need for a full, fair, phaseout of fossil fuels. The COP28 will not be considered successful or its hosts credible leaders in climate diplomacy if such a full, fair fossil fuel phaseout is not agreed. The Bonn talks made clear there is significant sophistication among both observers and low-emitting countries on options for consolidating this phaseout with an integrated and holistic use of the tools made available through the Convention, the Paris Agreement, and related mechanisms for international cooperation.

Adaptation (GGA)

The SB58 did not bring new clarity about a shared Global Goal on Adaptation. Parties remain divided over whether Article 7 of the Paris Agreement provides the defined goal or whether a more precise universal metric is needed, such as ‘zero harm to people or nature’.

While Bonn outcomes don’t specify these measures or provide for their being agreed in Dubai, discussions of global adaptation to climate impacts are becoming more consistent in recognizing the value of:

- sharing of information, technology, and financial resources;

- restoring ecosystems and safeguarding biodiversity;

- aligning policy, finance, and trade, with overall adaptation and resilience needs;

- accelerating decarbonization to reduce risk, harm, and cost;

- early warning, crisis response, and fiscal policy.

Adaptation action will require new kinds of finance, new areas of international trade negotiation, including around shared work on ecosystems and biodiversity protection. The major question remains open for COP28: Will the Parties be able to agree on language that sets an overarching Adaptation goal capable of orienting work in all areas for higher ambition, accelerated action, and cooperative implementation, including at the community level?

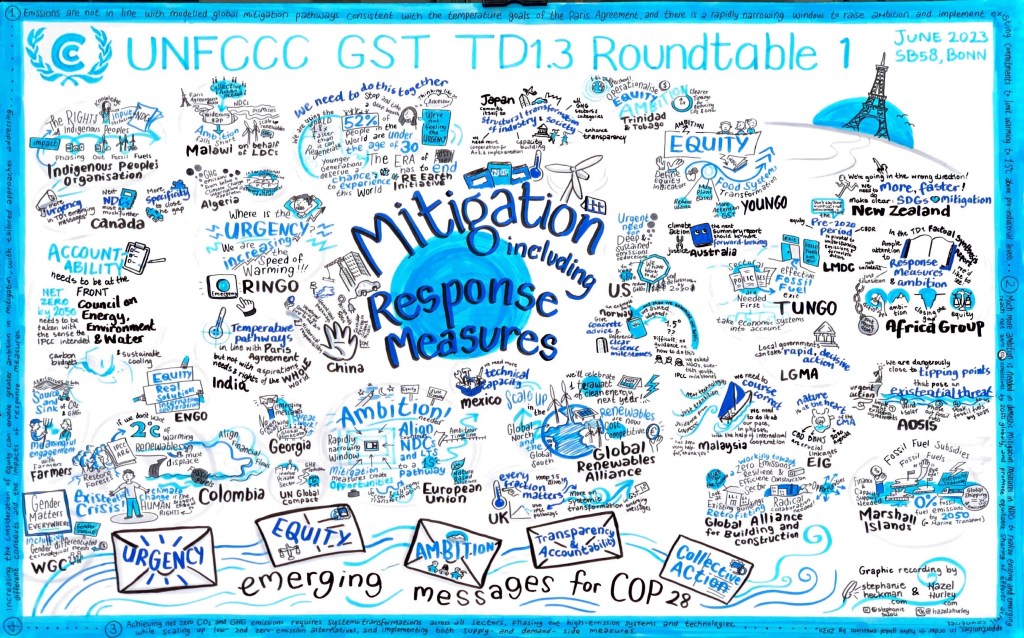

Global Stocktake (GST)

We are nowhere close to the level of mobilization needed to avert irreversible and worsening climate disruption. The Global Stocktake process is clear that this is the context in which Parties are now negotiating. The scientific findings of the IPCC are clear, and climate action to date remains insufficient. Around this, nations are agreed.

Where there is broad disagreement is on which nations carry which burden of immediate action to accelerate their own climate-related transition, and to support others in doing so. This subject has repeated brought discussions back to questions of finance, technology transfer, just transition, and cooperative approaches to accelerating progress.

A draft framework for the GST was published during the second week in Bonn. The framework outlines a detailed report on national and global progress. Carbon Brief highlights five key areas:

- Preamble;

- Context and cross-cutting considerations;

- Collective progress towards achieving the purpose and long-term goals of the Paris Agreement, in the light of equity and the best available science, and informing parties in updating and enhancing, in a nationally determined manner, action and support;

- Enhancing international cooperation;

- Guidance and way forward.

CCI will be emphasizing emerging opportunities for enhanced international cooperation, in line with IFI reform efforts and non-market approaches under Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement.

Finance (NCQG)

Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement calls for “strengthen[ing] the global response to the threat of climate change, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty” by:

“Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.”

This language is increasingly understood by all to mean: climate-related finance flows need to expand, become mainstream, reach beyond conventional financial interests, and get moving far more quickly, to support real-world solutions. The SB58 meetings showed increasing understanding of this fact, but did not deliver a new upgraded quantified goal to supersede the $100 billion yet to be delivered.

Discussions around the NCQG show increasing awareness among Parties that the overarching finance goal will need to be not just a number but a multifaceted, time-bound scaling strategy for delivering resources across diverse areas of need in all regions. Grounding the goal in lived experience will be critical, and there is not yet a mechanism in place for ensuring ongoing, detailed stakeholder participation to achieve that grounding.

Mobilization

Upgrading climate finance activities

Climate finance means different things to different people.

- For some, it means delivery of grants to support climate action.

- For others, it means development-related finance, primarily loans that advance funding but require repayment with interest.

- There is expanding interest in finance that does not operate through loans, or which leverages debt relief to create fiscal space.

- And, there are co-development strategies that can involve both financial and non-financial resources.

Climate finance activities need to do more than conventionally considered: We need vulnerability-sensitive debt relief. We need an overhaul of development finance arrangements. We need a significant increase in climate finance flows from public, private, and multilateral institutions. And, we need local and human-scale needs and priorities to inform high-level decision-making.

Increasingly, we are seeing the need for financial resources (‘money’ in most people’s thinking) to reach small-scale marginal actors and vulnerable communities that are underserved by or entirely detached from mainstream banking and financial institutions. This means technologies that can deliver financial resources digitally, or in micro-scale, will increasingly become part of the climate finance solution.

There is not clear mandate from SB58 for this work, but there is general agreement that financial innovation needs to be part of the solution.

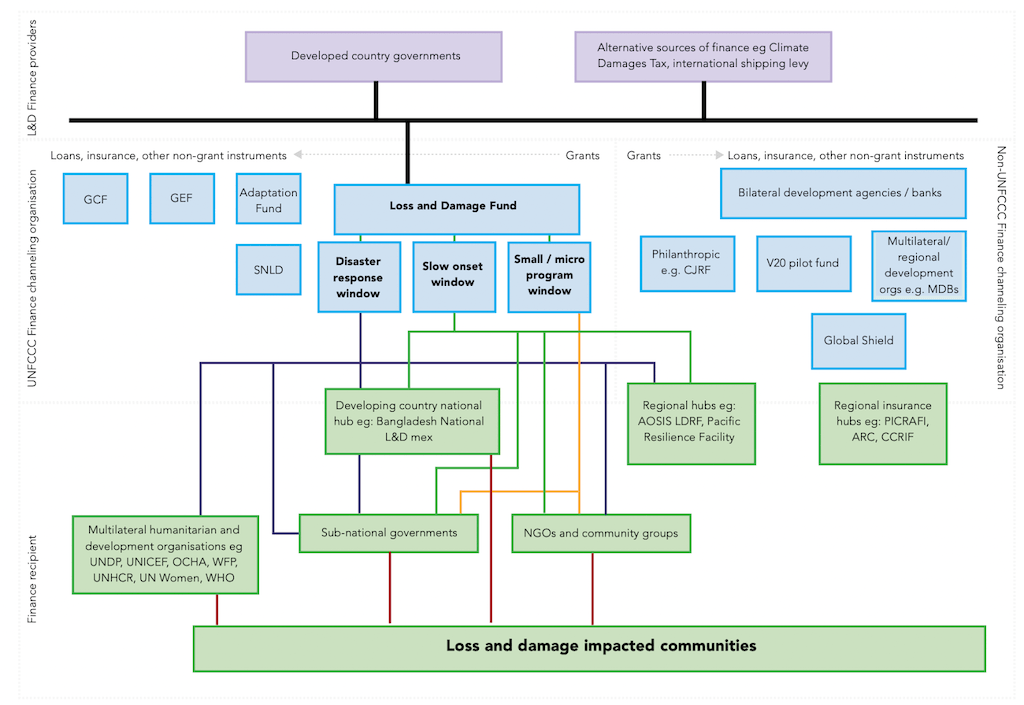

Loss and Damage

The work of the Transitional Committee advanced before and during the SB58, making it more likely there will be an agreed approach for establishing the Loss and Damage Fund.

- The Fund could operate across three levels: direct funding, related parallel funding arrangements, and expansion of loss and damage-response funding through existing institutions.

- How these modalities will take shape, on the way to, and during the COP28, remains an open question.

- The Paris Summit on a new global financial pact, ongoing reform of multilateral development finance, and the Bridgetown Initiative for vulnerability-sensitive debt relief may all play a role in unlocking the needed funding flows.

The integrated and holistic approach to Paris implementation, and to meeting the Convention mandate, is also driving more concrete awareness of the complex landscape of actors and actions needed to properly address and overcome loss and damage.

Key signs of progress in Bonn include:

- The Santiago Network and the Glasgow Dialogue are both now informing the work of the Transitional Committee, for the design and start-up of the Loss and Damage Fund, and for the wider landscape of work related to addressing and overcoming loss and damage.

- There are divisions, but these are about proportionality: There is general agreement that the Loss and Damage Fund will be only one piece of a broader puzzle, where new resources flow to vulnerable and affected communities to support recovery from climate-related losses.

- The need to recognize not just economic development losses but also potentially irreparable cultural losses is also now better understood and discussed in more practical detail.

International Finance Reform

A frequent topic in negotiations and in the halls, reform of international financial institutions is increasingly seen as a way to respond to and mitigate the fiscal and economic impact of climate change. Discussions in Bonn raised the following as ways to leverage IFI reform to accelerate climate-resilient development:

- Vulnerability-sensitive debt relief;

- Special Drawing Rights;

- Non-market approaches under Article 6.8;

- Co-development arrangements;

- Voluntary cooperative platforms to deliver multi-sector financial support across sectors and between scales;

- Innovative participatory design, delivery, and tracking of climate finance.

CCI has called for, and our network of citizen stakeholders has formally requested, international finance reforms that:

- Support for the Bridgetown Initiative;

- Advance human rights and gender equality;

- Welcome meaningful, ongoing citizen and stakeholder input;.

- Investigate direct delivery of funds to households, as a foundational support for climate-resilient development.

Food systems

The SB58 may mark the first time system-level transformation was openly discussed as the way to address climate-related agricultural innovation and food security risks and priorities. The Sharm el-Sheikh Joint Work on Implementation of Climate Action on Agriculture and Food Security recognizes the multidimensional and system-level impacts of policy and investment decisions related to food and agriculture.

As in other areas, there is some problematic slow-walking blocking progress. While sharing of information is moving ahead, direct linking of food and agriculture to Nationally Determined Contributions, National Adaptation Plans, and finance in all dimensions, has not been mandated, and may not be adequately tracked through the formal negotiating process.

This raises clear concerns about whether the pace of new investment into healthy, climate-resilient food systems will get up to speed. It also opens the space for informal multilateral multisector activities like the Co-Investment Platform for Food Systems Transformation, which will start initial operations in early 2024.

Cooperation and Engagement

Non-Market Approaches (including shifting incentives)

Article 6, paragraph 8 of the Paris Agreement aims to accelerate overall mitigation of global emissions (OMGE), by supporting national governments’ efforts to work together in an integrated and holistic way for mutual benefit and to produce wider benefits to climate, nature, and resilience. Three critical points about Article 6.8 can be helpful for understanding the scale of opportunity:

- ‘Non-market’ means ‘not emissions trading’ and so refers to virtually anything two or more countries might do to advance collective climate action.

- Article 6.8(c) calls for “coordination across instruments and relevant institutional arrangements”, which opens the way for active cooperation to align climate action with national and international commitments under other Conventions.

- There are effectively two tracks: a Paris track, in which all multilateral activity aside from emissions trading is welcomed; a Glasgow track, focused on sharing of information.

Progress at the SB58 focused on the Glasgow track: how nations will share information about existing, desired, and prospective non-market multilateral cooperative efforts.

- The emerging framework for sharing insights about and facilitating the start-up of non-market approaches should take into account the need for robust, diverse, and economy-wide climate-related transformation, aligned with real improvement to the everyday conditions of people and communities.

- There is agreement on creating a website for sharing insights on NMA activities, to launch in December, but there are still differences on how pro-active the NMA discussions should be in driving the creation of these multilateral cooperative arrangements.

CCI issued a deep dive policy brief on Non-Market Approaches as a substantive contribution to the Bonn negotiations.

Action for Climate Empowerment

Participation and engagement in the climate negotiations themselves can benefit from significant structural improvements. CCI consistently advocates for the evidence-based insight that enhanced inclusion and participation raises ambition and supports faster and more sustainable implementation of climate transformation policies and investments.

Article 6 of the Convention and Article 12 of the Paris Agreement formulate avenues for information sharing, transparency, education, training, cooperation, and civic engagement, described as Action for Climate Empowerment. These are ways of motivating ambition and keeping major economy-shaping actors inside and outside of government honest and future-oriented.

The negotiating process prioritizes the voices of Party representatives—diplomats speaking for national governments. Non-governmental voices are generally represented through non-negotiating interventions by a handful of formally recognized Constituencies. This means billions of people may be represented by a single person. While these interventions are often critically important and point to high standards for raising ambition and honoring human rights, they are insufficient to provide all of the useful and relevant insights stakeholders can provide to intergovernmental negotiations.

While there is not formal agreement on how this will proceed, or under the auspices of which body, the SB58 featured some discussion in virtually all areas of the process around the need for robust, detailed, ongoing stakeholder engagement—both to optimize the design of policies and investments and to track progress.

Mutual Accountability

Last year, the High-Level Expert Group convened by the United Nations Secretary-General issued its report Integrity Matters, calling for high standards and verifiability in the implementation of net zero commitments. The Integrity Matters report called for offsetting not to be used toward net zero commitments, but only as additional net emissions reductions after committed emissions reductions toward net zero are materially achieved.

All actors need better and more detailed information about how climate science insights, climate action policies, and climate finance commitments are playing out in the real world. The Global Stocktake is one piece of the mutual accountability puzzle. This includes the question of timeframes for which all countries are responsible: High-emitting countries should have been working to decarbonize since the Convention entered into force three decades ago; all countries also need to be building climate-resilient economies aligned with a low-emissions future.

Data systems integration and innovation—including the development of new, evolving, and multi-dimensional metrics for tracking delivery of non-financial benefits—will be critical for supporting both clear assessment of progress and evidence-based ratcheting up of ambition. Those data and metrics innovations will be linked to finance, capacity building, mitigation and adaptation activities, emissions trading and non-market approaches, and will naturally proliferate as appropriate to local and national needs.

Trade

For a long time, trade was seen as too complicated to be discussed in detail in the UNFCCC process. The intensifying frequency and gravity of climate impacts, however, has forced a change in that thinking. We now see climate impacts in all regions that threaten the stability of whole economies, undermining food security and creating real risk of climate-driven inflation.

Paragraphs 2 and 4 of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement provide means for trading of emissions. This will only be a narrow slice of overall global trade. Paragraph 8 of Article 6, by focusing on non-market international cooperation opens the door to addressing the climate resilience value of all areas of trade. Increasingly, we see conversations about finance, energy, adaptation, technology, data, and sustainable development including calls for climate-smart trade that benefits all trading partners.

The COP28 will be implicitly tasked with eliminating future climate damage from everyday trade relations—including in food, energy, and finance—even though the SB58 has not produced a definitive mandate to do so.

Prospects for COP28

The Road to COP28 is now becoming more clearly visible, and it is not a straight path. The COP28 will need to fill in many of the gaps described above, support consensus around major transformations that have not yet been fully agreed.

- The one all eyes will be on is the question of a full fair fossil-fuel phaseout. This much-needed step forward in global ambition will be the hard test of the incoming presidency’s diplomatic skill and future development strategy.

- Finance is a multidimensional challenge: A new overarching goal is needed; delivery on all existing commitments is needed; vulnerability-sensitive debt relief, cooperative fiscal space measures, and non-market approaches will all play a role.

- The integrated and holistic approach must mean raising of real-world ambition and mobilization for food systems, nutrition security, nature restoration, and the health and resilience of ocean ecosystems.

- Mainstreaming of climate-related finance, innovation, data-sharing, technology transfer, and resilience-building will have to be a key goal, manifested by breakthroughs in the mobilization of resources to catalyze economy-wide change.

In the coming weeks, we will hold internal discussions, debriefs, and planning meetings, linked to the Earth Diplomacy Leadership Initiative. UNFCCC participants and observers, or advocates and experts in related areas, can suggest inputs for these discussions, and for our future workshops, by emailing earth.diplomacy@citizensclimateintl.org

Resources

- For more information about Article 6.8 non-market approaches, please refer to the CCI-curated Article 6.8 Reading List: https://good.ctzn.works/a68

- For the long list of existing and prospective non-market approaches outlined ahead of the SB56, please refer to the May 2022 Synthesis Report on paragraph 6 of decision 4/CMA.3, prepared by the Secretariat. (PDF download)

- For information about the Glasgow Committee on Non-Market Approaches, the Work Programme, other aspects of Article 6.8 implementation, please visit the UNFCCC Cooperative Implementation page.

- For information about Article 6.8 meetings during the SB58, please refer to Item 15 on the SBSTA 58 provisional agenda.

- For possible emerging modalities for international non-market cooperative approaches to agriculture and food security, please refer to Item 10 on the SBI 58 provisional agenda.

- For Article 6.8 connections to cooperative financing for food systems transformation and related data systems integration efforts, read this Good Food Finance brief.

- Toward a global facility for good food finance – The Co-Investment Platform for Food Systems Transformation.

- Capital to Communities – The 2022 Reinventing Prosperity Report, includes information on engaging stakeholders in design and delivery of climate-related financial resources.

- Invest at the Source – report on investing to maximize integrated upstream-downstream co-benefits, from summit to seabed.

- Resilience Intel note on ocean health and resilience as critical to human health and wellbeing.

- Untapped Opportunities: Climate financing for food systems transformation – new report from the Global Alliance for the Future of Food.

- Integrated Data Systems Initiative – a five-year innovation sprint to transform food-related financial data.

- For a more detailed deep-dive into the substance of the SB58, outcomes, and perspectives from negotiators, read the Earth Negotiations Bulletin summary of the SB58, from IISD.

- On the Bridgetown Initiative – With clock ticking for the SDGs, UN Chief and Barbados Prime Minister call for urgent action to transform broken global financial system.

- On the Paris finance summit – Meaningful progress for relief to emerging economies, but more needed